It is a fact that not everybody likes scales! They can be seen as boring, repetitive and monotonous but they are the fundamental building blocks of nearly all the music we will ever play or hear. Granted, there are different styles based on different tonal centres, Schoenberg for example based his music on a scale that treated all notes equally, none of this tonic dominant nonsense for him.

For the main part, the music we are all accustomed to will be based on a major or minor scale or it’s derivatives, pentatonic, blues and all the modes. So why are they so important and how can students be inspired to learn them.

Scales are important because… Discuss

As we have already touched on, scales are the basis of nearly everything we play and hear, but they are often seen as just a way to pass an exam.

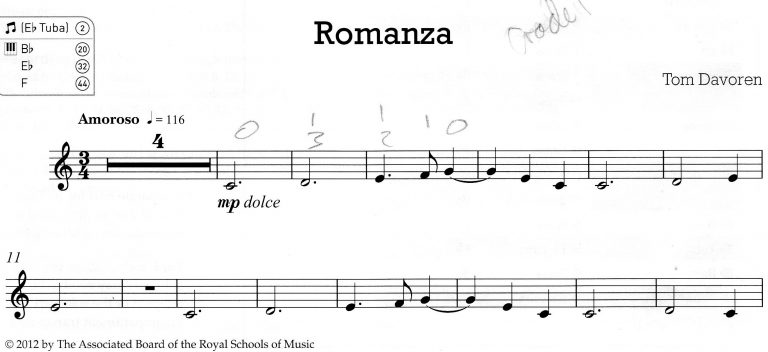

I suppose I must admit I was probably in that camp when I was interested in passing exams, but we are in a system where exams are seen as the aim of the students at the beginning of their journey. This is a bit of a shame because there are more things in our musical life than exams, and those who don’t get those opportunities to play in groups and with others seem to be missing out on something. But scales and arpeggios have great benefits to a player, firstly they establish patterns for the fingering or the slide so that when that appears in a piece of music it is second nature to play. A good example is the Grade 1 piece “Romanza” from “Shining Brass” book 1. The first five notes are C, D, E, F and G.

It is surprising when asked how many students don’t recognise the C major scale, but when it is brought to their attention the fingering is suddenly much more confident (thats if they can play a C major scale of course!). The next bar is a descending C major arpeggio, it’s all child’s play really.

That perfectly illustrates how scales and pieces are intertwined, so how do we persuade students to learn them?

Strategies

There are a couple of techniques to help make scales more interesting. The first is a well established technique of playing them in different ways, with different rhythms, perhaps jazz style or with a teacher playing bits of the scale and the student answering with the same or the next phrase. These don’t work with everyone though, and sometimes the best way is to just explain how they fit into the musical world and the context does the trick. Reading scales from a book is also a debatable solution. It is often the case that reading scales from a book is the wrong way of learning scales. A teacher needs to establish the best learning style for a pupil, and quite often when asked how they learn to use a new phone for example they will say they switch it on and try to press a few buttons and see if it works how they expect. If it does then they move onto another feature and try that it the same way. In my experience very few people read the whole book of instructions (often ebooks nowadays) before pressing a button. This kinaesthetic learning is, in my experience, the predominant way to learn, (although there are a small number who do read the manual before trying to use something (visual learner). So, if this is how they learn to use most other new things they come across, why do they think the visual approach ie. reading scales from a book, is going to be effective? One of the problems with this approach is that it will almost certainly go into the short term memory so that when it comes to trying to play it again, even only a short time later, it has been forgotten.

So we need to go back to where we started with scales, they are patterns of sound that can come in handy when playing music. If you can play a scale in Bb major then a piece in the same key will be easier to play, particularly if the piece has lots of scalic passages. It is probably good practice to discourage the reading of scales and arpeggios and encourage them to be worked out by ear. If a student recognises, or even can sing, a scale and they are familiar with the patterns it contains then it is relatively easy to practice by trial and error and try and work it out by making and correcting mistakes. The benefit of this is that once the patterns are established they are more likely to go into the long term memory where they will stick and be retained for the future.

On the other hand, if it proves impossible to memorise them this way and a book is necessary then so be it. The ABRSM and Trinity both produce books with scales in and are useful resources, but another option and possibly a more interesting one is to consider “Know your scales” by Paul Harris. The published version is for Trumpet but is suitable for most valved instruments. The composer has written various studies and tunes based on scales and arpeggios and is ideally suited for anyone who gets easily bored with scales. It is learning scales without realising that’s what is happening. One big omission though is that there still appears to be no version for Trombone in Bass/Tenor clef.

Conclusion

So scales are important because nearly all music we play will be based on them. They are important to establish patterns for fingering so that when they appear in a piece they are much easier to play and the panic that often ensues from these passages can be reduced. In this blog there are a couple of ideas for learning scales but if you have any other tips or strategies then please pass them on in the comments.